Let’s Cook Clean: Navigating E-Waste Management in Kenya and Rwanda

CLASP and the Modern Energy Cooking Services (MECS) bring new research into the e-waste management of electric cooking appliances in Kenya and Rwanda.

Increasing access to electricity, levels of disposable income, and growing urbanization are key contributors to the burgeoning number of appliances across most modern societies. For instance, the Kenya home appliances market attained a value of USD 184.48 million in 2018 and is projected to reach USD 363.92 million by 2027, growing at a compounding annual growth rate (CAGR) of 7.8%.1

This significant growth speaks to the urgent need to plan for proper management of potential e-waste resulting from the scale up of the appliance market. Proper management is crucial to avoiding any health or environmental consequences of e-waste and to taking proactive steps towards protecting individuals and their communities.

In Africa, less than 1%2 of e-waste is documented as collected and recycled properly. Even though many studies have been conducted on e-waste management, very few are in sub–Saharan Africa where most countries face significant e-waste management issues.

Loughborough University, through the Modern Energy Cooking Services (MECS) Programme worked with CLASP to conduct a research study on repair and end-of-life practices related to electric cooking appliances in Kenya and Rwanda. As the market for electrical cooking (e-cooking) products is only just taking off in many African countries, the study used televisions as a proxy for e-cooking, given their relatively mature market. The study provides insights into the ecosystem of the appliance market in both countries, how it operates, what happens to products at each stage of their end-of-life pathway, and the associated impacts.

In Africa, less than 1% of e-waste is documented as collected and recycled properly.

Taking Action: Consumer Behavior and Awareness on End-of-Life Appliance Management

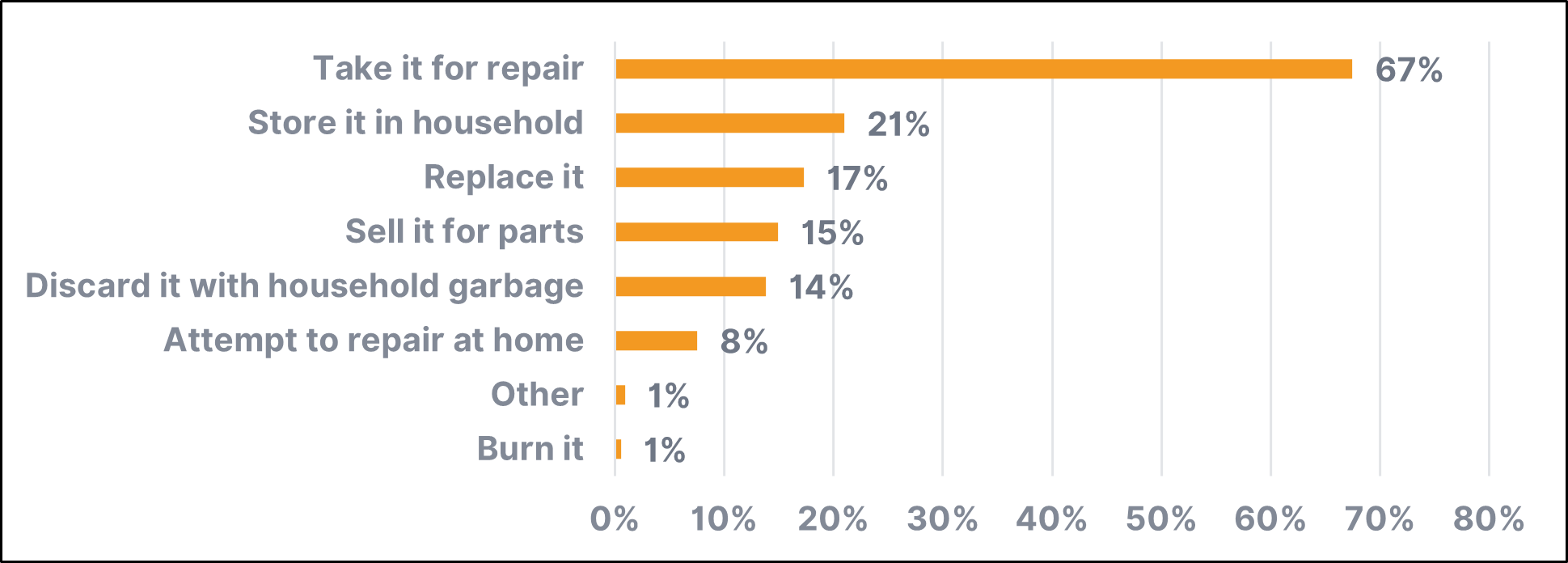

Unless externally incentivized, Consumers control the end-of-life pathway for their used electronics. This could be a formal drop-off point, informal waste collection, or storage within the home. Upon appliance failure, many consumers in both countries opt to take the appliance for repair, and this is predominantly conducted by informal local repair shops.

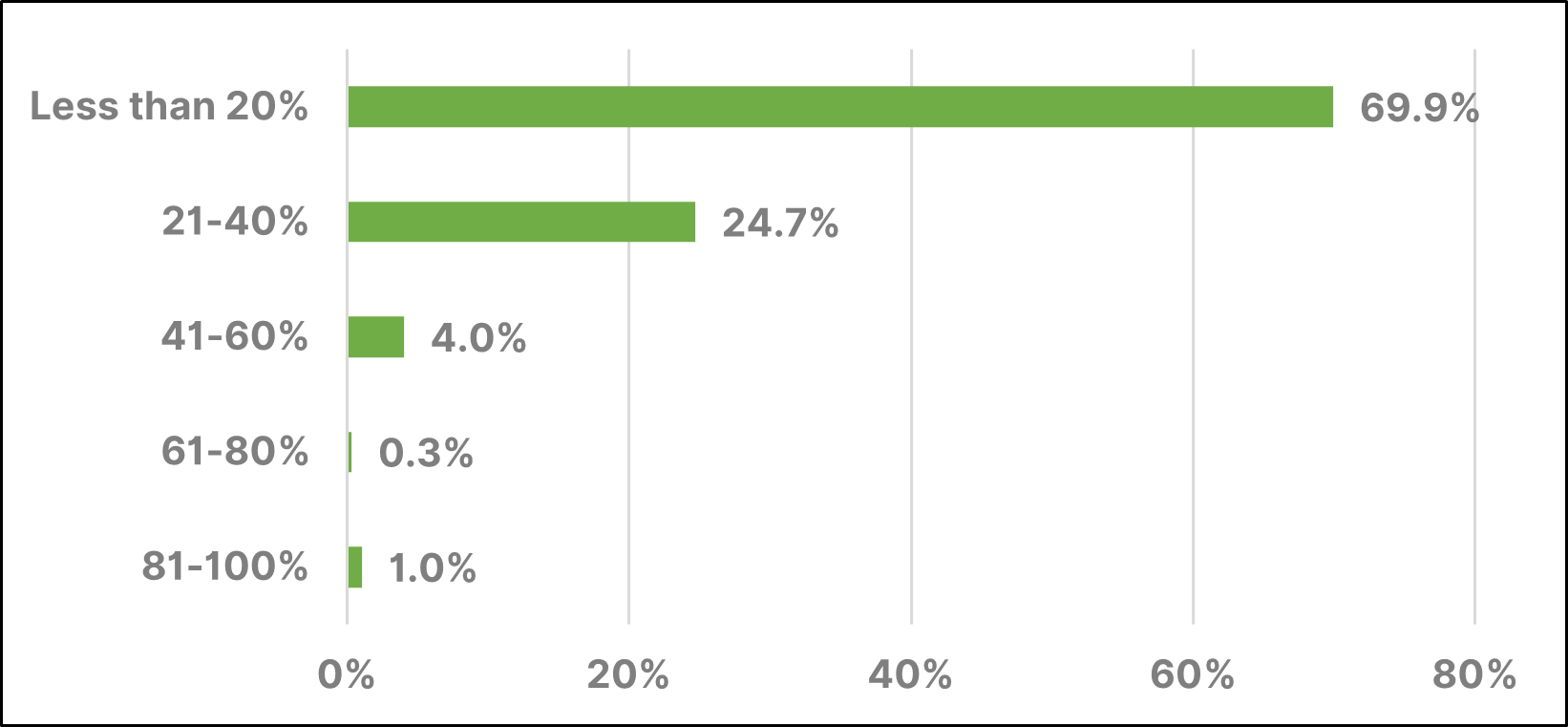

Overall, repair choices are most influenced by cost effectiveness. Consumers in Kenya who repair their appliances are willing to pay a service/repair fee of up to only 20% of the original appliance cost.

CLASP’s survey revealed that residents are generally more likely to store their non-functioning appliances in their households rather than to dispose or recycle properly, with 84% of respondents in Rwanda and 95% in Kenya reporting a lack of awareness on any designated e-waste disposal options in their communities. However, some consumers could better cite the dangers of improper e-waste disposal, indicating the benefits of awareness raising. Lilian Muthoni of the Usweni region in Kitui county in Kenya noted, “Kuna vitu hufai kuweka kwa nyumba, kama battery italipuka.” (There are things you should not store in your house, something like a battery can explode.)

A strong majority of the survey respondents that are using unsustainable practices expressed a willingness to switch to more sustainable behavior. In summary, awareness of environmental impact of poor e-waste disposal, financial incentives, and ease of disposal are the key factors that would promote more sustainable household behavior.

From Policy to Practice: Implementing E-Waste Regulations

Kenya has adopted several regulations that govern the quality and energy efficiency of appliances such as TVs, refrigerators, and off-grid solar (OGS) products. The Energy and Petroleum Regulatory Authority (EPRA) in 2013 initiated a mandatory standards and labelling (S&L) scheme covering lighting products, refrigerators, air-conditioners and motors, and the IEC quality standards for solar products. Similarly, the Rwanda Standards Bureau (RSB) has developed and published several standards for various electrical and electronic products, as well as a dedicated standard on e-waste management. These standards prescribe handling, collection, transportation, and storage of various categories of e-waste. Both countries are party to several regional and multilateral environmental agreements, including the Basel and Bamako Conventions.

Unfortunately, there is currently no information available quantifying the effectiveness of these schemes in keeping low quality appliances off the market. This gap in information may be due to the lack of clear practical guidance on how roles and responsibilities are distributed throughout the e-waste management ecosystem.3 This was evident in the feedback among surveyed e-waste stakeholders, where many had no awareness of the regulations that impacted them; those that did could not describe their effects.

Governments in sub-Saharan African countries are working to develop policies to mitigate further environmental harm, but often lack funding, expertise, and personnel to implement regulations. To achieve a green economy, both Kenya and Rwanda will need to bring together diverse stakeholders, allocate sufficient resources, and invest in awareness raising on proper e-waste management practices and infrastructure.

Keeping Stakeholders in Sync

The e-waste landscape in both Rwanda and Kenya reveals a complex ecosystem with an array of stakeholders, each with varying levels of influence and interests. Collaborative efforts are therefore pivotal in harnessing the potential of these stakeholders to drive sustainable e-waste management and foster a circular economy.

A significant proportion of these stakeholders operate within the informal sector, highlighting the importance of their involvement in decision-making processes and the development of initiatives. For instance, households commonly opt to take their malfunctioning appliances to informal repair shops. However, most times, these repair shops often face challenges related to limited technical expertise for advanced fault resolution and unavailability of spare parts, as Claude, an appliance repairer in Muhanga District in Rwanda said. Claude points out, “Sometimes, when a customer brings a phone, radio, or television to be repaired, we cannot help them because the spare parts are not available here. It would be better if spare parts could be made available in Muhanga or even Kigali.” This sentiment is not unique to Claude.

To support the e-waste landscape, for both formal and informal players, it will be useful to incorporate their perspectives in decision-making around key initiatives designed to develop the market (e.g., capacity-building programs, establishing accessible spare part markets etc.). Moreover, the research findings underline the potential for mutually beneficial relationships to flourish, particularly between formal and informal actors. There is great opportunity for governments to play a vital role in facilitating this collaborative relationship, such as exploring innovative measures and instruments to make the formal sector more accessible to informal stakeholders.

Grounding in Numbers: The Urgent Need for Data

The need for effective e-waste management policies and regulations is apparent, yet it hinges on a fundamental understanding of materials entering and leaving the ecosystem; this is grounded in data. Unfortunately, there is a lack of data on material flows in both Kenya and Rwanda, and the relatively small stakeholder sample used in the study did not offer precise estimates of quantities handled.

Furthermore, the majority of stakeholders, especially those in the informal sector, do not keep track of the amount of materials they handle. A notable example comes from Maina Gitau, a small-scale refurbisher in Nairobi, who found it difficult to pinpoint the number of appliances and materials he sells due to the constant turnover of his inventory. While he likely keeps records of revenue, tracking the precise quantity of materials passing through his shop daily remains a challenge.

To address these data gaps and ensure an accurate assessment of e-waste flows, both countries must establish systemic data collection frameworks. These frameworks should involve relevant government agencies, including those responsible for trade and industry, to track not only material flows, but also all stakeholders within the appliance value chains.

Crucially, such data collection initiatives will help monitor the impacts of transitioning to a circular economy, which, according to the International Labor Organization, could generate over six million jobs. Furthermore, these frameworks will simplify access to information on e-waste collection and processing facilities for the public, enabling a more informed and responsible action for proper e-waste management. Lastly, government agencies can leverage this data to support collaborations, funding efforts, and infrastructure development aimed at sustainable e-waste management.

Summing it Up

Understanding end-of-life practices for appliances is pivotal in establishing sustainable frameworks for responsible disposal and for promoting the broader mission of circularity. The recommendations derived from our studies in Rwanda and Kenya hold promise far beyond these borders. By implementing robust awareness campaigns, enforcing e-waste regulations, and establishing systemic data collection systems, countries in sub-Saharan Africa can take substantial steps toward responsible e-waste management. May this study serve as a catalyst for others to continue conducting research on e-waste landscapes across sub-Saharan Africa and beyond.

The full publications for this study on Rwanda and Kenya can be accessed on the MECS website.

Explore related work and initiatives in circular economy and clean cooking that CLASP has completed, such as the Bending Toward Circular report and Use and Impacts of Electric Pressure Cookers report. Additionally, be on the lookout for our forthcoming projects, including a reparability index study for solar appliances, which will provide valuable insights into the evolving landscape of sustainable practices and offer opportunities for collaboration in our shared mission towards a more sustainable future.

2. 3. ACE-TAF, Best Practices and Challenges in implementation of E-Waste Policy and Regulatory Framework in Rwanda, 2021.