Insights into Energy Efficiency in Rio’s Favelas

‘Energy Efficiency in the Favelas’ report reveals new details about the impacts of energy inefficient services on residents in Rio de Janeiro favelas.

The Sustainable Favela Network (SFN), Favelas Unified Dashboard, and RioOnWatch are initiatives of the NGO Catalytic Communities (CatComm).

In preparation for Earth Day (April 22), Rio de Janeiro’s Sustainable Favela Network (SFN) and the Favelas Unified Dashboard (PUF) launched Energy Efficiency in the Favelas. The report details community access to energy efficient appliances, services, and habits, as well as highlights opportunities for government intervention. CLASP provided training to the researchers on topics in energy-efficiency.

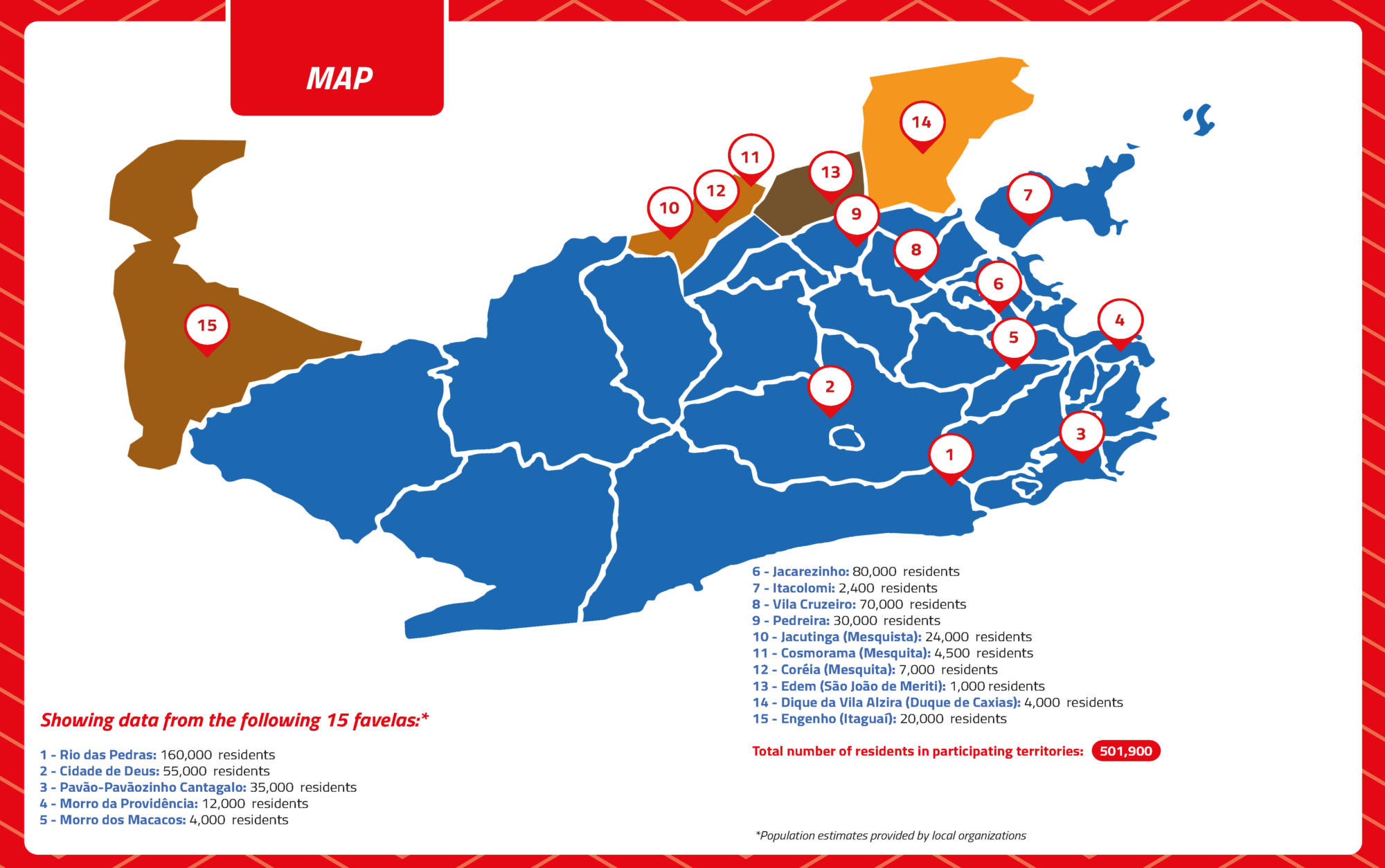

Last year, the SFN, PUF, and seven partner institutions implemented the course and research project, ‘Monitoring Water and Energy Justice in the Favelas.’ The course and resulting research engaged 45 youth and leaders from 15 favelas in Greater Rio as citizen-researchers. The findings demonstrate how favelas can produce robust data, often eliciting deeper insights than researchers and utilities from outside the communities.

Map of Greater Rio de Janeiro, showing where the research took place.

Following the launch of the initial research project report Water and Energy Justice in the Favelas: Data Collected Make Inequalities Evident and Lead to Demands for Change—released in September 2022, with coverage in Globo TV, CNN, Agência Brasil, and Notícia Preta—participants turned their attention to more in-depth and detailed analyses of their data on energy efficiency. One outcome is the new report launched today.

New Data on Energy Efficiency in Rio’s Favelas

The data presented in the new report Energy Efficiency in the Favelas reflect the reality of 1,156 families (4,164 people) in 15 favelas from five municipalities across the Greater Rio metropolitan region, and specifically show the relationship between energy, poverty, and social inequality, focusing on the efficiency of service provision and use.

Kayo Moura, a social scientist, student of statistics and member of the data and narratives laboratory, LabJaca, based in the Jacarezinho favela and recently referenced in The New York Times, was responsible for the analysis.

He explains:

“The most interesting thing [about this study]… was understanding that when we talk about energy efficiency in the favelas, urban peripheries, and the Global South, we are talking about justice, about access. If I had to define the report in one statement, it would be that: energy inefficiency operates as a tool of energy injustice, especially in Brazil’s favelas.

Inside favelas, with a majority of families left socially vulnerable, inefficiency affects the poorest of the poor. It is those with the least knowledge of social programs, such as the Social Electricity Tariff, that suffer the most from service inefficiency and endure the most frequent and longest blackouts.”

The data can serve as a reference and impetus for policymakers to support vulnerable families become more energy-efficient through improved access to energy-efficient appliances outright or larger subsidies.

The Backdrop of Poverty and Racial Inequality

Energy Efficiency in the Favelas presents the data within the socioeconomic context of community members. For example, of the 4,163 residents represented in the data, over half the families interviewed live below the poverty line.

The analysis also looked into racial breakdown by income bracket: there was a clear inverse correlation between race and income. A smaller proportion of Black people were present in higher income groups, reflecting the broader societal trend of Afro-Brazilians being overrepresented in lower income brackets.

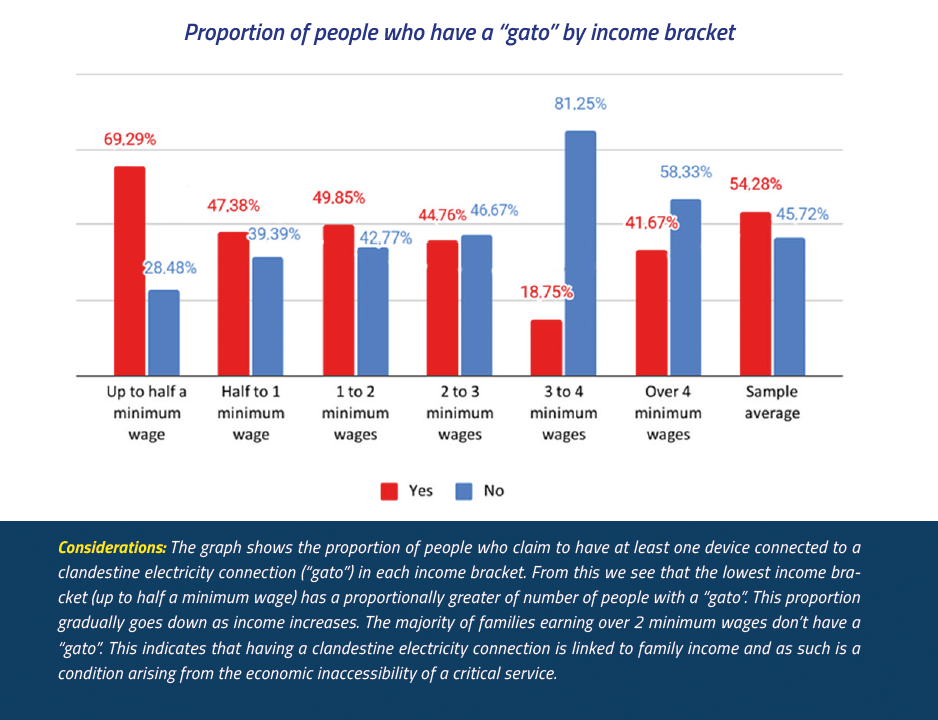

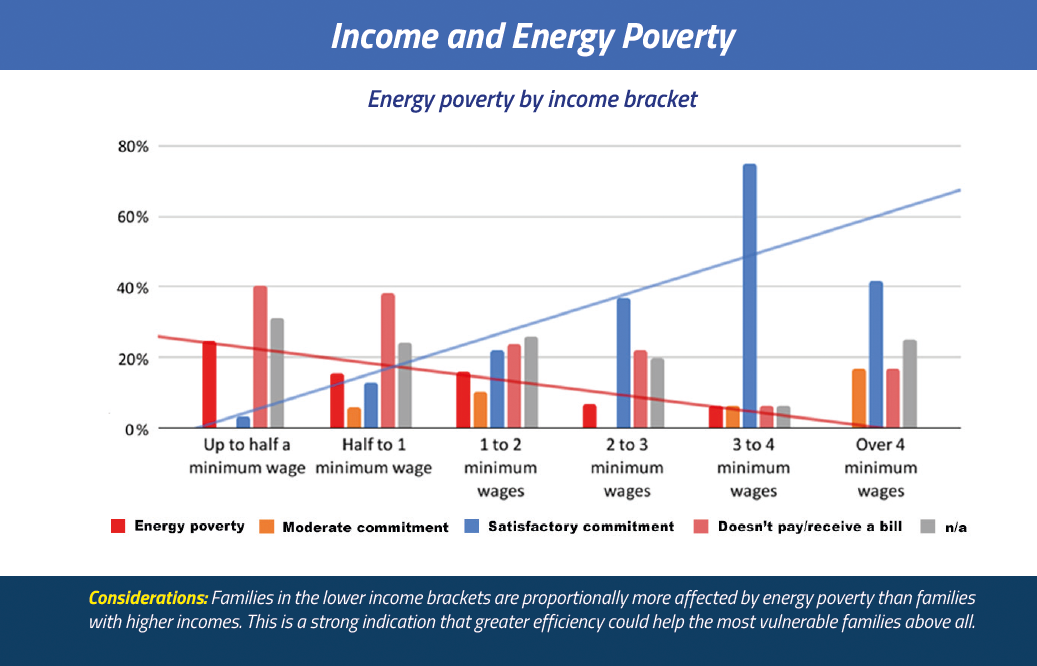

The Daily Reality of Energy Poverty

Energy poverty refers to when an electric bill takes up over 10% of a family’s monthly income (the recommendation is below 6.8%). The report shows that families earning zero to half a minimum wage comprise the majority of families facing energy poverty. There is a trend line: as the income bracket increases, the proportion of families facing energy poverty decreases.

Additionally, 69% of respondents stated that if their electric bill were halved, they would use the money to buy food (instead of paying other bills, buying medication, for education, etc.), which indicates that energy poverty is directly linked to food insecurity for interviewees.

Families in energy poverty must seek alternative means to access critical electricity – in the favelas, ‘gatos’ (clandestine electrical connections) are a common approach. As Moura explains:

“The approach we used when studying ‘gatos’ was from the perspective of understanding the need to guarantee access, rather than criminalize access. The data show how ‘gatos’ are frequently the only means by which people can access energy. The poorest families are shown to have the biggest proportion of ‘gatos.’ As income increases, the proportion of those who state they do not have a ‘gato’ also increases. So we see how this is a question of access, of being in a financial position to pay the electric bill, and not one of dishonesty or taking advantage.”

Depending on the irregular connection of a “gato” results in inefficiency of access to the service and repair, further reinforcing the poverty of the family. The families with the lowest incomes in the study were those that suffered most from service inefficiency. Moura summarized the results:

“Those who said they faced daily blackouts are in the lowest income brackets. As the income bracket increases, the number of people stating they did not face a blackout that lasted over 24 hours in the past three months also increases.

Favela Residents Lack Choice & Information on Efficient Appliances

Energy-efficient household appliances provide the same or improved services while using less energy, resulting in cost and energy savings. The research aimed to understand whether favela participants have access to efficient appliances, as well as what types and which appliances have the largest impact on their electric bills.

Obtaining information about energy-efficient appliances that could potentially reduce electricity bills is challenging for lower-income families. These families reported the lowest levels of awareness about the National Energy Conservation Label (ENCE), a mandatory label affixed to all electrical appliances in Brazil, which indicates their energy usage in comparison to other appliances.

Qualitative accounts revealed that energy-efficient appliances, often the latest models, are expensive and are therefore inaccessible to residents. Lower-income residents reported that their appliances break down quicker due to recurring blackouts and they must replace them regularly with second-hand ones.

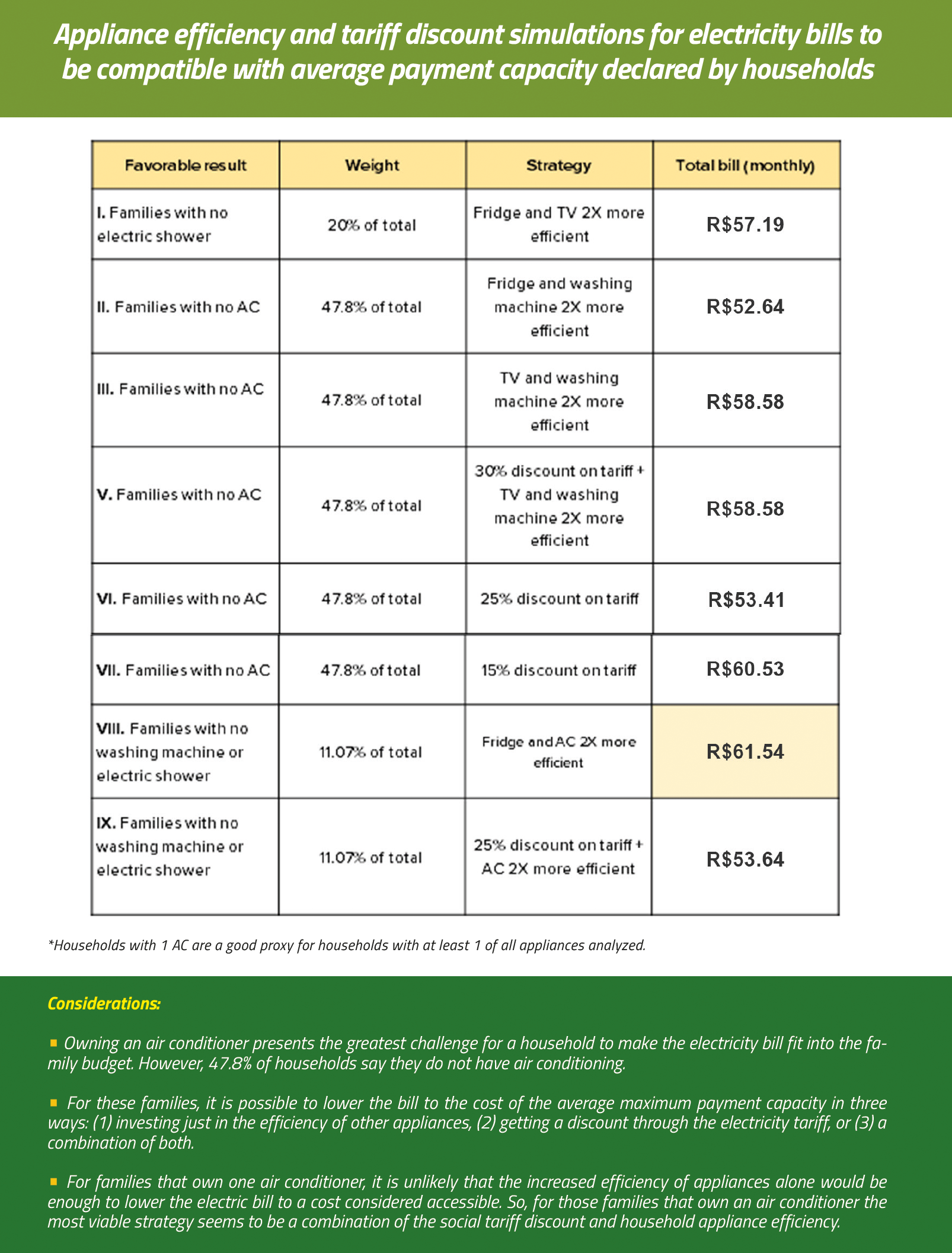

The study focused on key household appliances (air conditioners, electric showers, refrigerators, washing machines, televisions, and fans) and calculated the estimated impact of each appliance’s energy consumption on a family’s monthly income. The research confirmed that air conditioners are the highest energy consumer and have the biggest impact on the household budget, despite the benefits on increasingly hot days in Rio.

Air conditioners account for 51.4% of total electricity consumption, surpassing the combined impact of electric showers, refrigerators, washing machines, televisions, and fans. Over 50% of those interviewed reported owning between one and three air conditioners.

According to Moura, this part of the survey aimed to assist authorities and professionals to identify ways to help families achieve more efficient average energy consumption:

“While it may not be feasible to produce an air conditioner that is three times more efficient, could it be possible to implement a social tariff that offers a 25% discount to families that meet a specific criterion and use air conditioning, for example?”

Efficient Habits Independent of Clandestine Access

There are two main strategies to achieve efficient energy use. The first is to invest in efficient appliances, which, as demonstrated, is a challenge for favela residents due to high upfront costs and lack of awareness. The second is consumer habits.

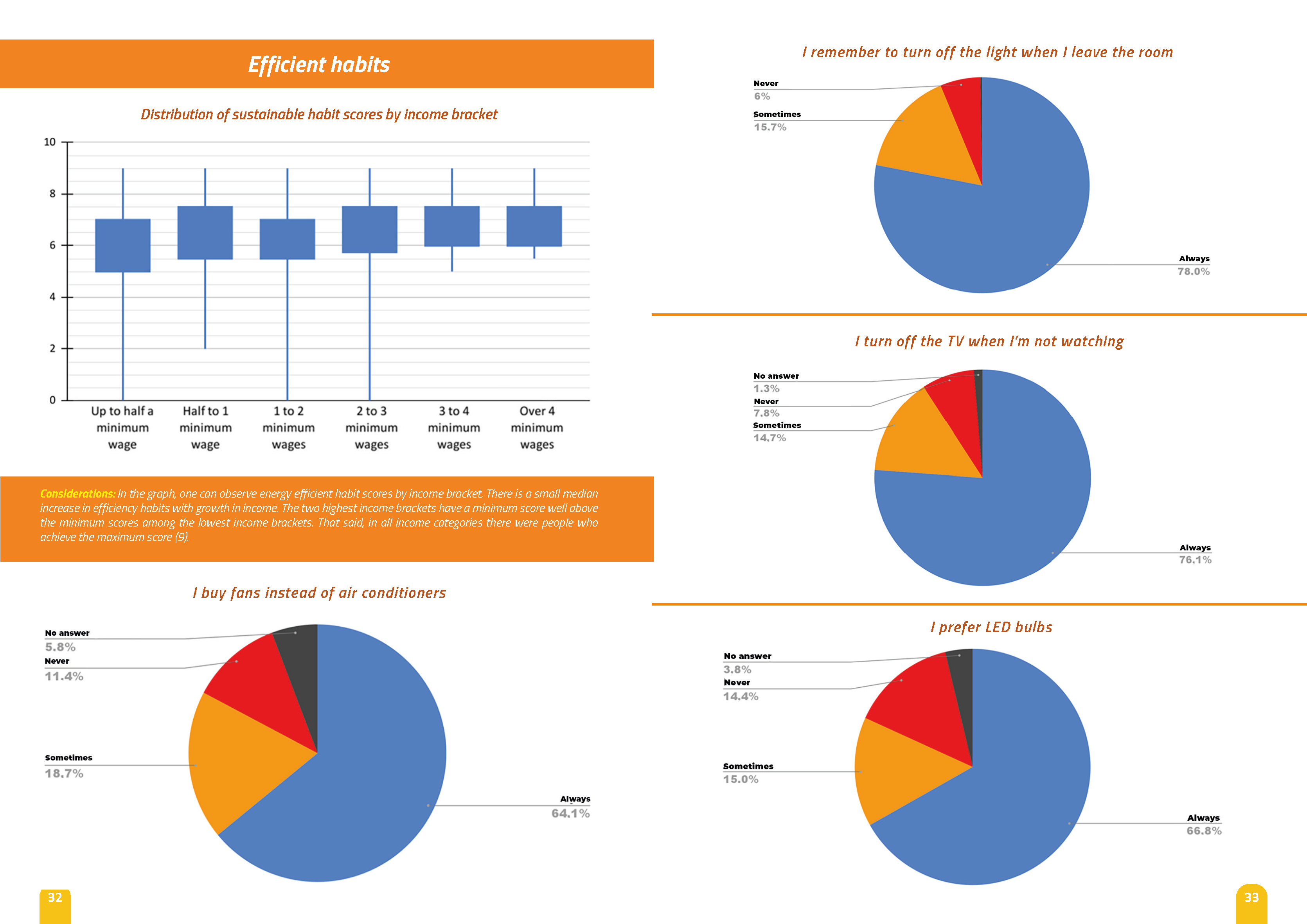

The study aimed to understand consumer habits around efficiency: such as remembering to turn off lights when leaving a room or using LED bulbs. Based on the responses, the researchers developed a point system. The system attributed one point to every response that represented a high degree of energy efficiency, with the highest score being 9. The results show a high degree of concern about maintaining efficient habits: over half of interviewees scored between 6 and 9, and many showed concern with having energy efficient habits without even knowing the term.

Moura summarizes:

“There’s a myth that no one in the favela cares about energy-saving habits. There’s also a misconception that everyone in the favela has a ‘gato’ [clandestine electric connection] and that since they don’t pay for electricity, they don’t care about savings or energy efficiency. We compared the behaviors of people who have a ‘gato’ and those who don’t. We discovered that there is a small difference between those who have a ‘gato’ and those who don’t, but that it’s negligible, indicating that, in general, regardless of whether a person has a ‘gato’ or not, residents tend to seek energy efficiency in what is in their power: their habits.”

Poor Awareness of Available Social Energy Services

The study sought to understand community members’ awareness of the Social Electricity Tariff (TSEE) and the ENCE label. The Social Tariff offers discounts on electric bills and provides rewards for energy savings: the more efficient the consumer is, the larger the discount. Both mechanisms aim to make bills cheaper for families with the greatest need.

As with the ENCE label, the study found that there is a significant lack of knowledge about the Social Tariff. This was seen in all income brackets during the study, but over 75% of lowest income groups do not know the program exists. Approximately 60% of families in the study meet the income criteria for the TSEE, but only 8% state that they receive the benefit. Of the families that meet income criteria to qualify for the TSEE, 90% say they do not receive the benefit.

For the Community, By the Community

Through the research, CatComm aimed to demonstrate the benefits of community-led research. It can be challenging to elicit honest responses about topics like gatos if residents fear potential repercussions from outside researchers. The insights garnered by Moura and his team are robust; community members opened up more easily to the youth researchers based on established trust.

“People from outside often see the favela as a problem, which is why the study we’ve conducted is crucial: it’s by the favela, for the favela. We are no longer objects of study; we are building our own narrative from the inside out, producing discourse about ourselves,” explains Moura. “There’s no way of thinking and talking about the favela without us being there as the main actors, as subjects. We’re here telling our own story. It’s no longer someone else telling it from the outside. This is why electricity is important, because the lack of electricity also means the lack of means of communication. e can speak for ourselves, so we can tell our own story. The story of Brazil from our point of view.”

Highlights from the Data

Efficiency and Quality of Access

- 55.2% of people represented in the research are living below the poverty line, with a per capita monthly family income of up to R$497 (US$96).

- 41.5% of families earning up to half the minimum wage experienced blackouts lasting over 24 hours in the past three months. Among families earning 2-3 minimum wages, the percentage was 23%.

- 32.1% of families have experienced loss of electrical appliances due to electrical grid failures.

- Families pay, on average, an electricity bill that is twice their average payment capacity. 31% of families experience energy poverty, with a disproportionate amount of the family budget going to pay the electric bill.

- 69% would choose to spend the savings on food if their electric bills were reduced.

- 68.7% of those interviewed (794 people) do not know what the Social Electricity Tariff (TSEE) is. 59.55% of families meet the income criteria to qualify for the Social Tariff, but only 8.04% of families state they receive the benefit, while 90.04% of families who would qualify affirm they do not receive it.

- 73% of families earning up to half a minimum wage state they do not complain or make requests to the utility, Light. As income increases, comfort in requesting services from the utility increases: only 33% of those earning over four minimum wages say they do not make complaints to Light.

Energy-Efficient Appliances and Habits

- Air conditioning is responsible for over half (51.4%) of energy consumption in the sample, followed by electric showers (13.8%) and refrigerators (13.6%).

- Energy-saving habits are at a good level across the sample population. The average score was 6.21 and the mode was 7, with the scale ranging from 0 to 9. Among those interviewed, 78% always remember to turn off the lights when leaving a room and 67% choose LED bulbs.

- 50.6% state they know what the National Energy Conservation Label (ENCE) means. Of those that know the label, 49.1% state they have bought an electrical appliance based on it being classified in the ENCE A category.

Read more

- Energy Efficiency in the Favelas Report in Portuguese

- Energy Efficiency in the Favelas Report in English

- Energy & Water Justice Article

- Energy & Water Justice Report

- Documentary

The course “Researching and Monitoring Water and Energy Justice in the Favelas,” was carried out collaboratively by the following organizations: Roots in Movement, ICICT and EPSJV (Fiocruz), Climate and Society Institute, CLASP, LabJaca, DataLabe, and Casa Fluminense.

The community organizations which took part in the course and research project were: Alfazendo (City of God/Rio de Janeiro), Fusion Social Center Association (Jacutinga/Mesquita), Women of Attitude and Social Commitment Association (Dique da Vila Alzira/Duque de Caxias), Edson Passos Women’s Association (Cosmorama/Mesquita), Association of Itaguaí Warrior Women and Social Organizers (Engenho/Itaguaí), Life Root Community Center (Morro dos Macacos/Rio de Janeiro), Transvida Cooperative (Vila Cruzeiro/Rio de Janeiro, LabJaca (Jacarezinho/Rio de Janeiro), Maria Pimentel Marinho Women’s Movement (Itacolomi/Rio de Janeiro), Museu de Favela (Cantagalo, Pavãozinho e Pavão/Rio de Janeiro), Grassroots Social Education in Solidarity Economy Nucleus (Coréia/Mesquita); Inclusion Project (Edem/São João de Meriti), Projeto Moleque (Pedreira/Rio de Janeiro); Sowing Love Social Project (Rio das Pedras/Rio de Janeiro), SOS Providência (Providência/Rio de Janeiro).